How do MIT undergraduate students regulate their learning to achieve their academic goals?

Project Overview

The Learning Strategies Assessment (LSA) Project is a research study developed by the MIT Teaching + Learning Lab to understand how MIT students manage their time/effort, cognition, motivation, and wellbeing over the course of a semester to achieve their academic and personal goals. The LSA Project aims to inform efforts across the MIT campus to support students’ learning, engagement, and work-life balance.

Background

We developed the LSA Project in response to stories shared by MIT students through the Flipping Failure initiative. Many Flipping Failure participants have shared stories about the academic challenges they faced at MIT and the strategies they used to overcome them. Through these stories, it became apparent that there was a need for more information about how MIT students manage their learning processes to achieve their academic and personal goals. While researchers have identified effective learning strategies and methods for supporting students’ self-regulated learning, MIT is a unique learning environment. We felt that TLL’s work, as well as that of many other members of the MIT community, would benefit from having more data on MIT students’ self-regulated learning strategies.

To address this need, we developed a self-assessment tool – the Learning Snapshot survey – that enables students to reflect on the strategies they have used to manage their learning processes. We are currently collecting data to validate the Learning Snapshot survey and investigate the relationships between MIT students’ self-regulated learning strategies and their academic and personal outcomes. In the near future, we hope to incorporate a feedback component into the Learning Snapshot survey, allowing participants to receive a summary of their answers, feedback on their approaches to learning, and resources that can be used to enhance their learning processes.

Research Objectives

Research Objective #1: Develop a new self-assessment tool, the Learning Snapshot survey, to capture MIT students’ self-regulated learning strategies (that is, strategies for managing time and effort, cognition, motivation, and wellbeing) at different points in an academic term.

Research Objective #2: Examine how students’ self-regulated learning strategies are associated with outcomes such as academic performance, personal goal attainment, and burnout.

Research Objective #3: Explore how students’ goals and self-regulated learning strategies might differ by academic discipline and level.

Methods

When designing the research methods for the LSA Project, we examined the research literature on self-regulated learning, metacognition, and related constructs (e.g., Kim et al., 2020; Panadero, 2017; Pintrich & DeGroot, 1990; Pintrich et al., 1993; Wolters, 2003; Wolters & Brady, 2021; Zimmerman, 2002; Zusho, 2017); reviewed existing measures of self-regulated learning and learning strategies (e.g., Kim et al., 2018; Pintrich & DeGroot, 1990; Schraw & Dennison, 1994); and conducted semi-structured interviews with a sample of currently enrolled MIT undergraduate students during the 2022–2023 academic year.

Measures

Based on the results of our literature review and qualitative data collection, we decided to focus on four hypothesized components of self-regulated learning: time and effort, cognition, motivation, and wellbeing. The first three components—time/effort, cognition, and motivation—are commonly recognized as aspects of self-regulated learning in the research literature. We added the fourth component¬—wellbeing—in response to results from the qualitative interviews with MIT students, which suggested that students’ strategies for managing their sleep, energy, stress, and anxiety were often closely linked with their self-regulated learning processes.

Learning Snapshot survey

The Learning Snapshot survey was designed to capture the ways in which students managed their time/effort, cognition, motivation, and wellbeing over a 7-day period. Many items on the Learning Snapshot survey were sourced from established measures of self-regulated learning (e.g., Kim et al., 2018; Pintrich & DeGroot, 1990; Schraw & Dennison, 1994) and adapted to fit MIT’s unique learning context. In addition, new items were developed to reflect constructs that emerged from qualitative interviews with MIT students. The Learning Snapshot survey asks students to report on their learning processes over the past seven days to reduce the likelihood of recall bias. Distributing the Learning Snapshot 2–3 times a semester allows researchers to examine the ways in which self-regulated learning strategies may vary at different points in an academic term.

Intake survey

The Intake survey was developed to gather information about students’ activities during the semester to examine the ways in which students’ semester goals and activities (including their academic workload, co-curricular activities, and other commitments) might be associated with different patterns of self-regulated learning during the semester.

Outcomes survey

The Outcomes survey was developed to measure students’ perceptions of their semester outcomes and examine the associations between students’ self-regulated learning and outcomes, including both academic outcomes (such as engagement and achievement) and personal outcomes (such as perceptions of goal attainment and burnout). We also requested permission to use students’ academic records to assess their semester achievement.

Pilot Data Collection

The first full-scale data collection effort for the LSA Project was conducted during the fall 2024 semester. We invited 1,200 randomly selected undergraduate students to participate in the study and gathered the following data from these participants:

- An Intake survey, which asked students to provide information about their fall semester activities and to identify up to three goals for the fall semester.

- Two Learning Snapshot surveys, each of which asked students to report on their approaches to managing their learning over the past 7 days.

- An Outcomes survey, which asked students to report on their fall semester outcomes.

- Academic records (e.g., grades/GPA, credit hours) from students who provided us with consent to use these data for research purposes.

We are currently repeating this data collection effort for the fall 2025 semester.

These pilot data will be used to address initial questions about MIT students’ goals, self-regulated learning strategies, and outcomes. They will also be used to evaluate and refine the Learning Snapshot survey, which we hope to make available to students more widely in subsequent project years.

Intake Survey

Snapshot Surveys

Outcomes Survey

Timing

Early semester

Snapshot I: Weeks 9–10* Snapshot II: Weeks 12–13*

End of semester

Measures

- Academic workload

- Co-curricular activities

- Other time demands

- Fall semester goals

- Demographics

- How time was spent (past 7 days)

- Regulation strategies (past 7 days):

- Time

- Cognition

- Motivation

- Wellbeing

- Additional measures (past 7 days):

- Procrastination

- Academic engagement

- Goal attainment

- Academic engagement

- Burnout

- Satisfaction with grades, learning, and strategies

Distributed to

Random sample of 1200 undergraduate students

All intake survey participants

Participants who submitted at least 1 Snapshot

Fall 2024 Participants (Response rate %)

321 (26.8%)

1. Mid-semester: 275 (85.7%)

2. Late-semester: 266 (82.9%)

255 (85.3%)

Fall 2025 Participants (Response rate %)

TBD

1. Early-semester

2. Mid-semester

3. Late-semester

TBD

Key Findings

GOALS: What types of goals did students set for the fall semester?

Data Source(s): Intake Survey (Fall 2024)

On the Intake survey, we asked participants to submit up to three goals that they would like to achieve or make progress toward during the fall semester. Students could set any type of goal (e.g., academic, career, personal).

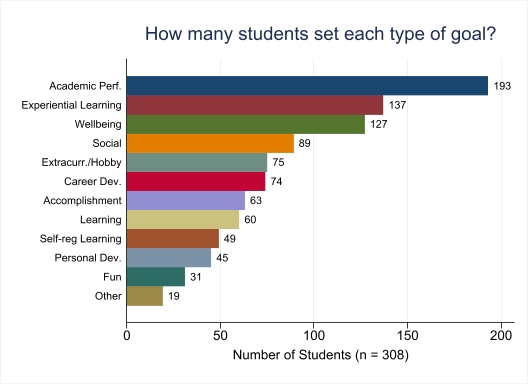

In fall 2024, 308 students submitted 853 fall semester goals. To examine the types of goals that students set, a member of the LSA research team coded students’ goals into 12 categories. Goals could be coded into more than one category. We then examined the proportion of students who set each type of goal at least once.

Note: Students could enter up to three goals, and goals could be coded into more than one category.

The most common types of fall semester goals included academic performance goals, experiential learning goals, wellbeing goals, and social goals.

- 62.7% of participants set an academic performance goal. These goals referenced students’ performance in their classes, including specific grades that students aimed to achieve in one or more classes, minimum GPAs that students wanted to attain/maintain, and general references to “passing” or “doing well in” classes.

- 44.5% of students set an experiential learning goal. These goals referenced engaging in hands-on learning activities, including more formal activities (UROPs, internships, building teams) and personal projects or hobbies that involved building or making things (e.g., building a website, making a physical object).

- 41.2% of students set a wellbeing goal. These goals referenced improving or maintaining one’s physical, mental, and/or emotional wellbeing. Common examples included getting more or better sleep, managing stress/anxiety, improving work-life balance, and establishing healthy eating or exercise habits.

Other types of common goals

- Social goals (28.9%)

- Extracurricular/hobby goals (24.4%)

- Career development goals (24.0%)

- Accomplishment goals (20.5%)

- Learning goals (19.5%)

Less common but notable

- Self-regulated learning goals (15.9%)

- Personal development goals (14.6%)

- Fun goals (10.1%)

TIME/EFFORT: Which time management strategies were most/least commonly used by students?

Data Source(s): Learning Snapshot I and II (Fall 2024)

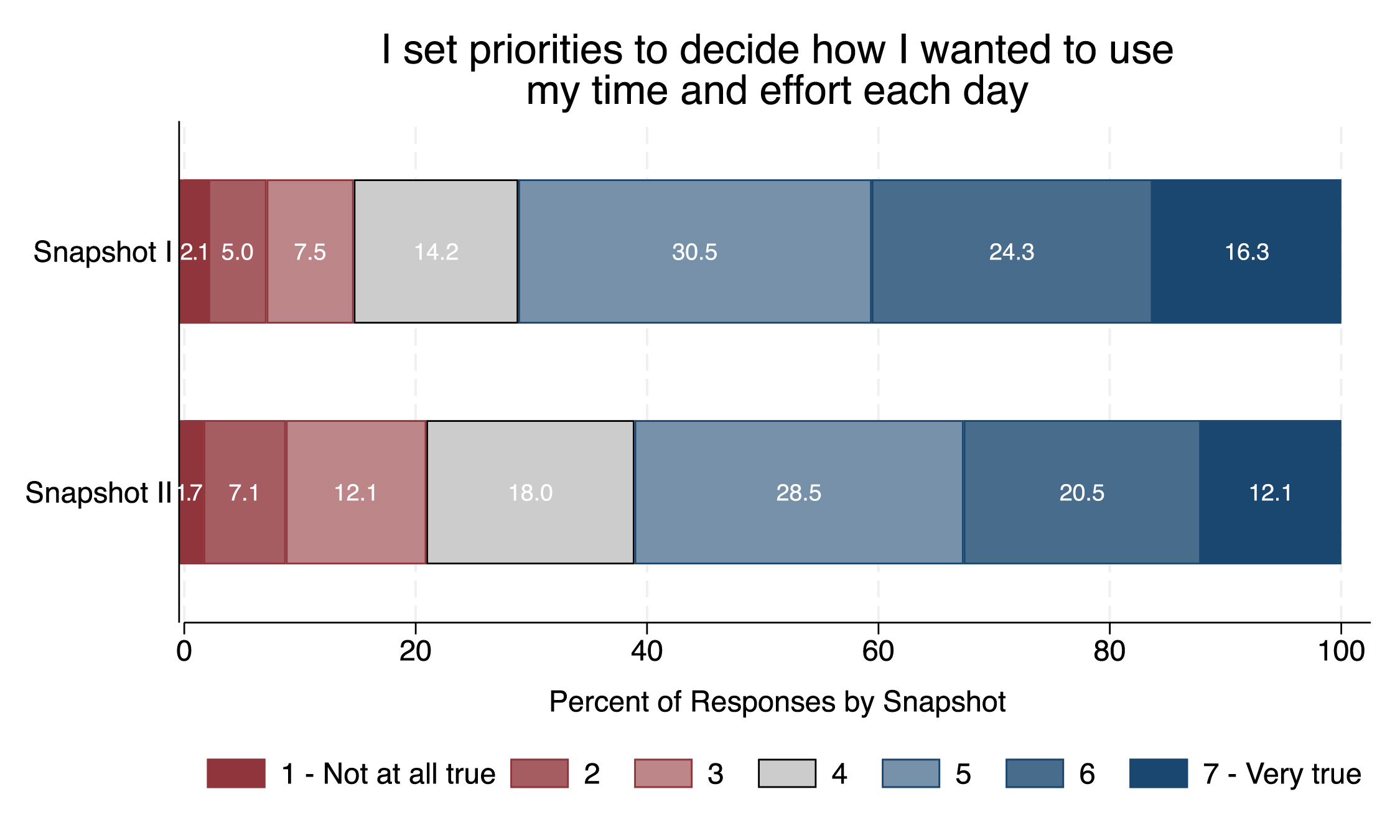

The most highly rated items on the time/effort regulation scale referred to prioritizing between multiple time demands and adapting plans to complete important tasks.

- Most students (see Figure 2) reported setting daily priorities to decide how they wanted to use their time and effort, although the proportion of students who reported using this strategy decreased somewhat from Snapshot I (71.1%) to Snapshot II (61.1%).

- Around three-quarters of students reported that they were able to adapt their plans as needed to accomplish their goals (73.8% at Snapshot I, 74.5% at Snapshot II).

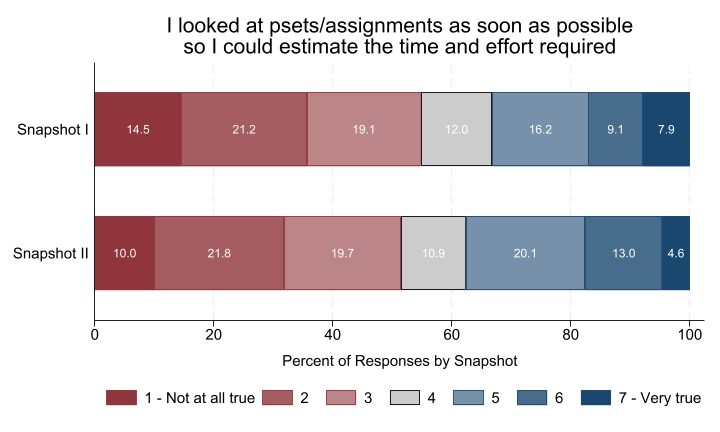

Fewer students reported using strategies that involved estimating the time needed for upcoming assignments or breaking down complex tasks into smaller components.

- On both Snapshot surveys (see Figure 3), only one-third of the respondents indicated that they had looked ahead at upcoming assignments to estimate the time/effort required (33.2% at Snapshot I, 37.7% at Snapshot II)

- Fewer than half of the respondents reported breaking complex/difficult tasks into smaller, more manageable pieces at both time points, although the proportion of students who reported using this strategy increased somewhat from Snapshot I (40.3%) to Snapshot II (48.5%)

COGNITION: How did students manage their focus and attention while engaging in academic tasks?

Data Source(s): Learning Snapshot I and II (Fall 2024)

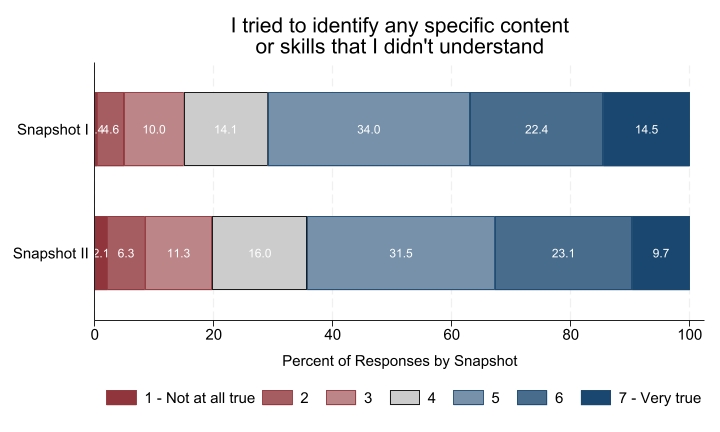

The most highly rated items on this scale referred to ways in which students could self-assess their knowledge and skill level while engaging in academic tasks.

- Most students (71.0% at Snapshot I, 64.3% at Snapshot II) reported that they had tried to identify specific content or skills that they did not understand while engaging in academic tasks in the past week (see Figure 4).

- A similar proportion of students (63.5% at Snapshot I, 64.7% at Snapshot II) indicated that they had tried to identify areas where they needed more review or practice.

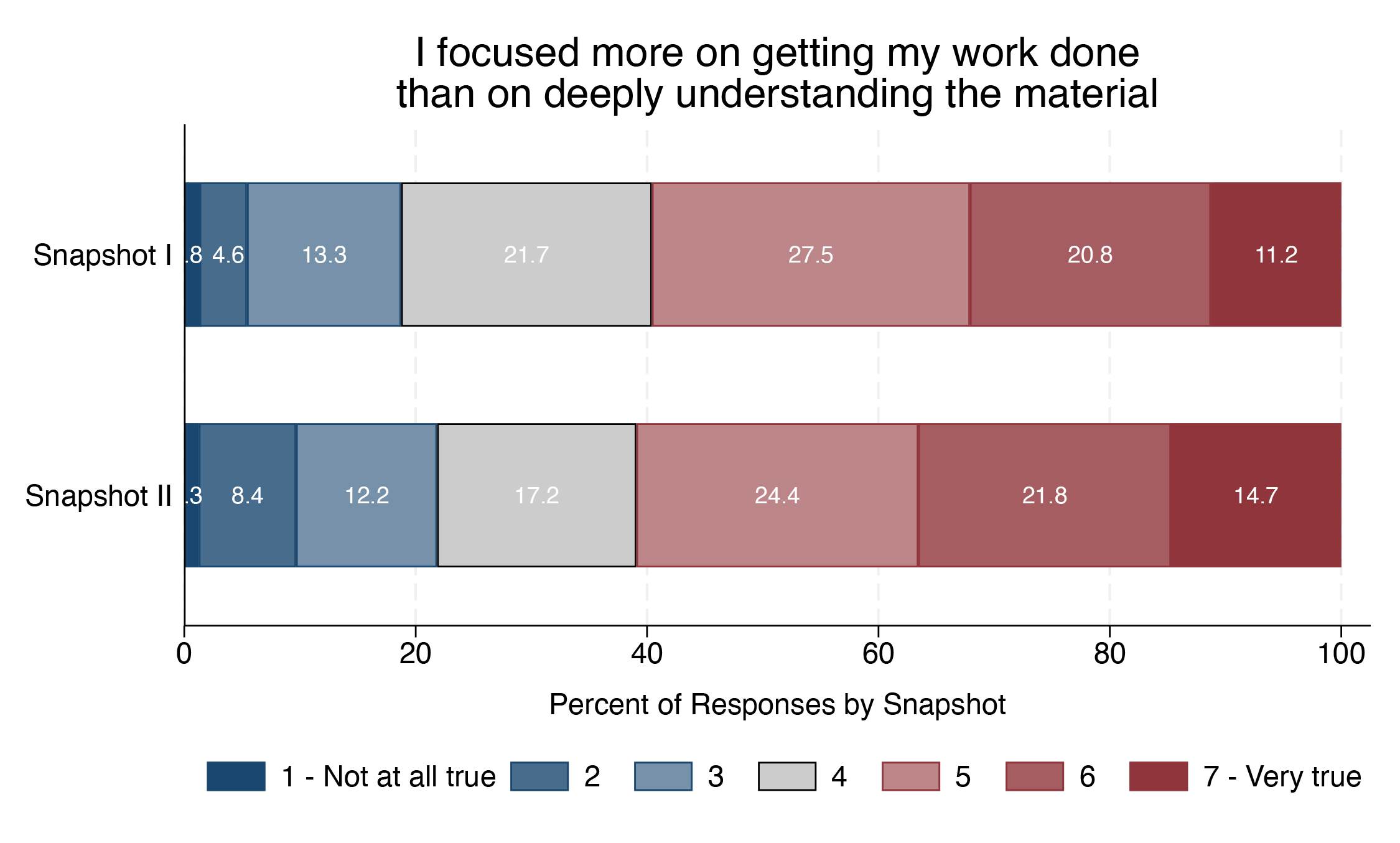

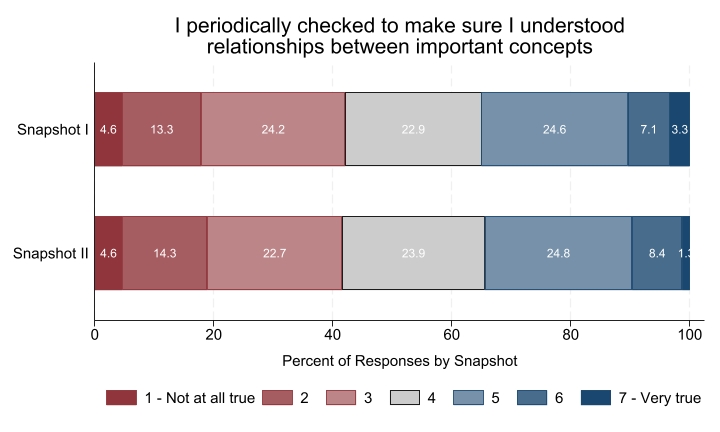

However, students’ responses to some items on the Snapshot surveys pointed to a possible tension between deeper learning strategies and time demands:

- Many students (59.6% at Snapshot I, 60.9% at Snapshot II) reported that they were more focused on completing their work than on deeply understanding the material (see Figure 5).

- Meanwhile, relatively few participants (35.0% at Snapshot I, 34.5% at Snapshot II) reported that they had checked to make sure that they understood relationships between important concepts (see Figure 6).

Note: The colors on this graph are reversed to reflect the fact that this item is negatively worded.

MOTIVATION: How did students motivate themselves to engage with academic tasks?

Data Source(s): Learning Snapshot I and II (Fall 2024)

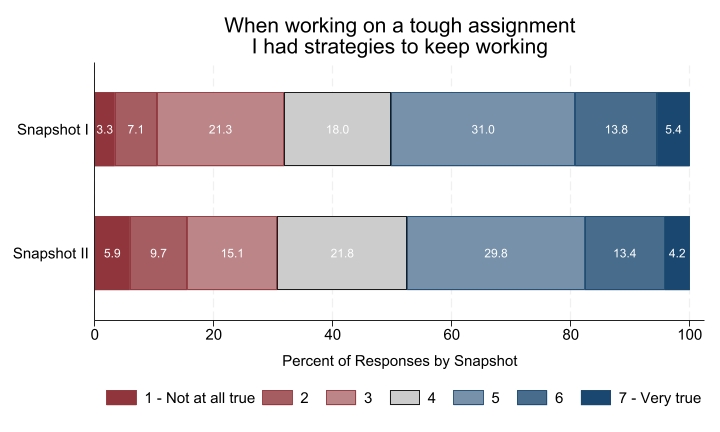

We saw significant variability in students’ responses to most items on the motivation regulation scale. The most highly rated items referred to students’ persistence in the face of difficult academic tasks.

- Around half of the participants at each time point (50.2% at Snapshot I and 47.5% at Snapshot II) indicated that they had strategies to continue working on tough assignments (see Figure 7) and were able to stick with studying when it was hard (52.5% at Snapshot I and 49.4% at Snapshot II).

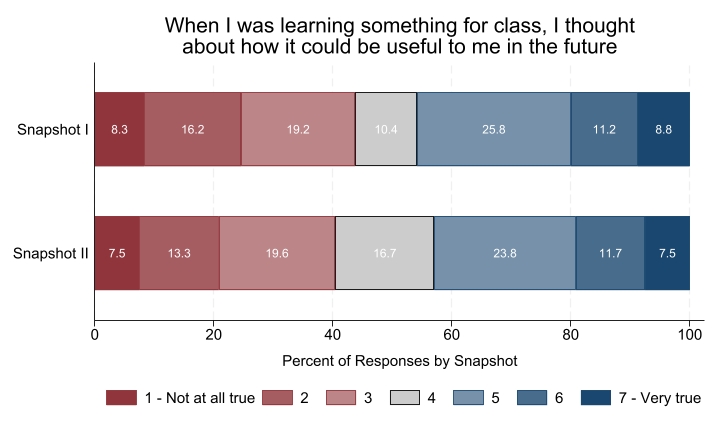

A slightly smaller number of respondents described being able to foster their motivation by focusing on what was interesting, useful, or enjoyable about what they were learning.

- Fewer than half of the participants at each time point (45.8% at Snapshot I and 42.9% at Snapshot II) reported that they thought about how the material they were learning in class could be useful to them in the future (see Figure 8)

- A slightly smaller proportion of students (41.0% at Snapshot I, 38.7% at Snapshot II) reported attempting to identify something interesting about what they were learning in each of their classes.

WELLBEING: What were the most common challenges that students experienced in managing their wellbeing?

Data Source(s): Learning Snapshot I and II (Fall 2024)

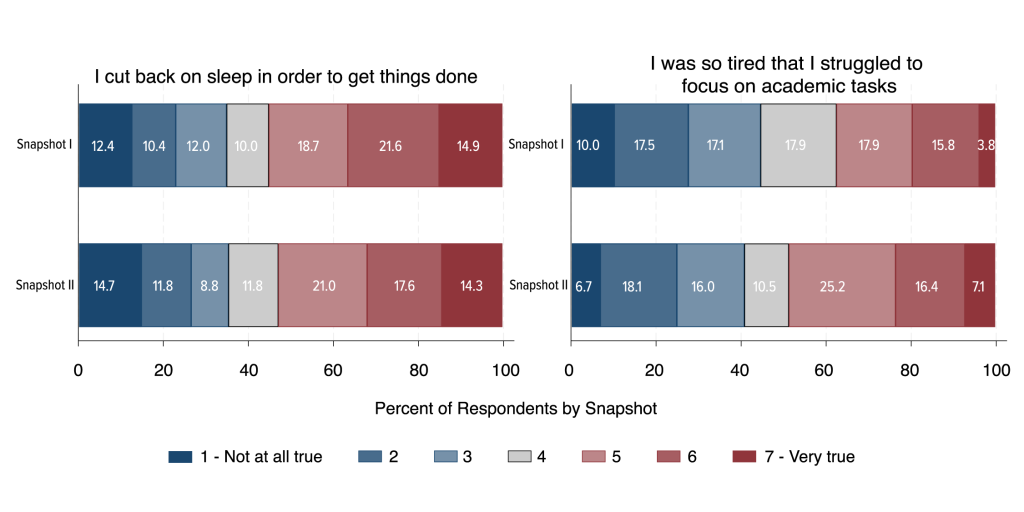

Sleep and energy

Sleep seemed to be a challenge for many students, although there was considerable variability in students’ responses to items that referenced sleep habits.

- More than half of the respondents on each Snapshot survey (55.2% at Snapshot I and 52.9% at Snapshot II) indicated that they had cut back on sleep in order to get things done over the past week (see Figure 9).

- The proportion of students who said that low energy levels interfered with their ability to focus on academic tasks increased from just over a third (37.5%) at Snapshot I to nearly half (48.7%) of the respondents on Snapshot II. (see Figure 10).

Note: The colors on Figure 9 and Figure 10 are reversed to reflect the fact that these items are negatively worded.

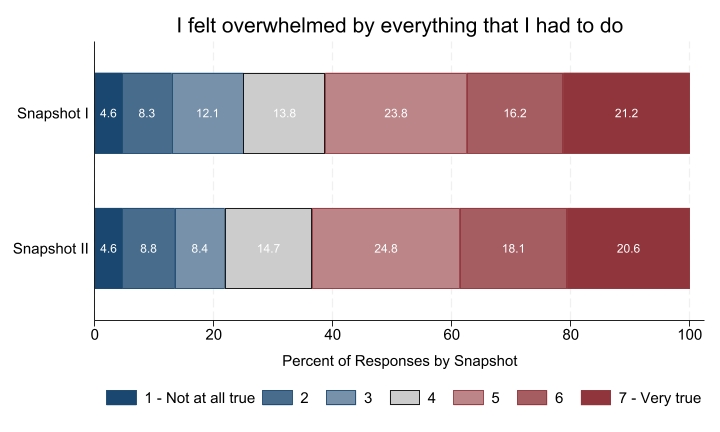

Note: The colors on Figure 11 are reversed to reflect the fact that these items are negatively worded.

Stress

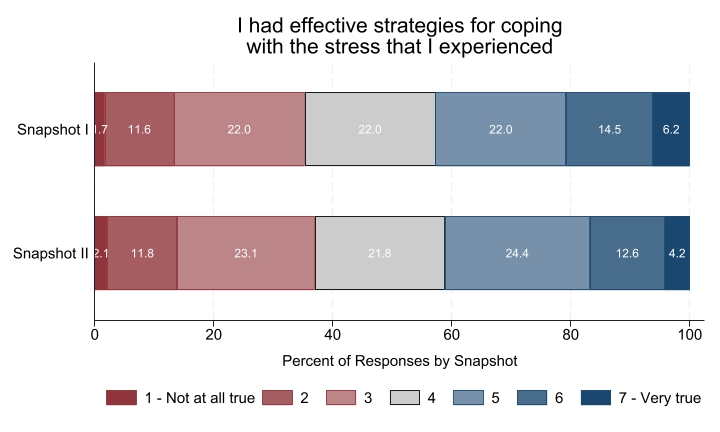

Students’ responses to items on the wellbeing scale also pointed to concerns about stress.

- Over half of the students (61.3% at Snapshot I, 63.5% at Snapshot II) reported feeling overwhelmed by the amount of work they had to complete during the past week (see Figure 11).

- The use of coping strategies to manage stress varied (see Figure 12). While a significant proportion of students (42.7% at Snapshot I, 41.2% at Snapshot II) reported having effective strategies for dealing with stress, over one-third of respondents (35.3% at Snapshot I and 37.0% at Snapshot II) indicated that this was not the case for them over the past week

How to Learn More

Members of the MIT community can request custom data reports and presentations from the LSA Project Data to enhance their teaching and learning practices. If you are interested, please get in touch with Dr. Amanda Baker, Associate Director of Research and Evaluation.

References

Kim, Y., Brady, A., C., & Wolters, C. A. (2018). Development and validation of the brief regulation of motivation scale. Learning & Individual Differences, 67, 259–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2017.12.010

Kim, Y., Brady, A. C., & Wolters, C. A. (2020). College students’ regulation of cognition, motivation, behavior, and context: Distinct or overlapping processes? Learning & Individual Differences, 80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2020.101872

Panadero, E. (2017). A review of self-regulated learning: Six models and four directions for research. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00422

Pintrich, P. R., & De Groot, E. V. (1990). Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom academic performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82, 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.82.1.33

Pintrich, P. R., Marx, R. W., and Boyle, R. A. (1993a). Beyond cold conceptual change: the role of motivational beliefs and classroom contextual factors in the process of conceptual change. Review of Educational Research, 63, 167–199. doi: https://doi.org10.3102/00346543063002167

Schraw, G., & Dennison, R. S. (1994). Assessing metacognitive awareness. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 19, 460–475. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1994.1033

Wolters, C. A. (2003). Regulation of motivation: Evaluating an underemphasized aspect of self-regulated learning. Educational Psychologist, 34(8), 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3804_1

Wolters, C. A., & Brady, A. C. (2021). College students’ time management: A self-regulated learning perspective. Educational Psychology Review, 33, 1319–1351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09519-z

Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(2), 64–70. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1477457

Zusho, A. (2017). Toward an integrated model of student learning in the college classroom. Educational Psychology Review, 29(2), 301–324. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44956378