Rigor as Inclusive Practice

On Thursday, October 6, 2022, we hosted Drs. Jamiella Brooks and Julie McGurk to discuss how inclusive teaching, by definition, promotes academic rigor.

Redefining Rigor

In her opening remarks, Dr. Jamiella Brooks noted that their work on the relationship between rigor and inclusion evolved when they observed instructors often incorrectly associating inclusive teaching with less rigorous course practices. Although the word rigor does not have an accepted single definition in academe, it has traditionally been equated with a highly challenging, inflexible curriculum with heavy workloads requiring extensive reading and studying. Brooks and McGurk observed that many educators hold misconceptions about inclusive teaching, that it is a “softer” or more “touchy-feely” approach to teaching that may require lowering academic standards and less rigorous learning activities. These misconceptions (about rigor and inclusion), Brooks and McGurk explained, are why we need to rethink how rigor is defined.

Brooks and McGurk argued that incorrect assumptions that rigor and inclusion are in opposition lead to teaching practices that are neither inclusive, equitable, nor rigorous. In fact, evidence suggests that true inclusion necessitates rigor to empower all students to grow, build on their strengths, and learn. Indeed, when we are teaching in inclusive and equitable ways, Brooks and McGurk argue, we are raising the rigor for us (in our teaching practices) and for students (in their learning). To illustrate rigor as inclusive practice, they presented three guiding principles that challenge inadequate definitions of rigor and help frame a more positive and productive connection between rigor and inclusion (Nelson, 2010).

Key Principles

- Rigor, when defined apart from a deficit ideology, is necessary to teach more inclusively.

- Inadequate definitions of rigor produce poorer learning outcomes, particularly for underrepresented and/or underserved students.

- Rigor is not simply hard for the sake of being hard, but it is purposeful and transparent.

I. Rigor, when defined apart from deficit ideology, is necessary to teach more inclusively

Deficit ideology is one of the sources of misconceptions around rigor. Brooks explained that traditional ideas about rigor draw on deficit models that attempt to explain and justify differences in achievement based on assumptions about what students lack rather than systemic issues that limit students’ opportunities to build requisite knowledge and skills to succeed. Brooks described a study by Fullilove and Treisman (1990) that examined the achievement of first-year African American and Asian American scholars in mathematics. Although many instructors observed in the study assumed differences in student performance were attributable to lack of effort, the authors found that the differential performance could be minimized by applying strength-based strategies rather than deficit ideology. They created an honors program that taught students to develop effective learning strategies and to build community with other scholars. By shifting the assumptions from student deficits to their access to study groups and skills, the honors program successfully lowered withdrawal and failure rates (Fullilove & Treisman,1990).

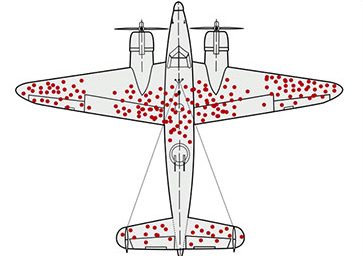

Misconceptions about rigor based on a deficit ideology may be due to a logical error known as survivor bias – our own biases as ‘survivors’ of an inequitable system. To illustrate, Brooks drew on a well-known study conducted during World War II to find which areas on a plane were most vulnerable to anti-aircraft fire by examining areas of damage on planes that survived enemy attacks. They initially assumed that the areas with the most bullet holes would need additional armor. However, this analysis overlooked the critical damage that occurred to the aircraft when they did not survive an attack. In the same way, we may look back at our own educational experiences with rigor as survivors and not recognize the damage done to those left behind.

Illustration of hypothetical damage pattern on a WW2 bomber. Based on a not-illustrated report by Abraham Wald (1943), picture concept by Cameron Moll (2005, claimed on Twitter and credited by Mother Jones), new version by McGeddon based on a Lockheed PV-1 Ventura drawing (2016), vector file by Martin Grandjean (2021).

So, how do we define rigor as inclusive practice? McGurk highlighted a recent study by Culver, Braxton, and Pascarella (2019) that emphasized rigor as enacted through assignments and in-class practices that require a higher-order understanding of course content. Culver first noted the inadequacy of definitions of rigor related to heavy workloads by highlighting the inequities it creates, particularly for students who encounter accessibility issues with course materials, have work or family responsibilities, and struggle with time management. In courses with rigor, defined as a higher-order understanding of concepts and skills, students reported that they are more likely to employ critical thinking, appreciate the skills and ideas of the discipline, and enjoy the challenge of the class (Culver et al., 2019). This study highlights the importance of distinguishing between workload and higher-order thinking in definitions of rigor.

II. Inadequate definitions of rigor produce poorer learning outcomes, particularly for underrepresented and/or underserved students.

Inadequate definitions of rigor may lead to the use of weak evidence for assessing student learning. For example, if rigor is defined as simply “hard,” then low grades or failing students could be used as “proof” of a more rigorous curriculum.

McGurk challenged these assumptions and instead argued that the grading scheme of a course needs to be aligned with adequate definitions of rigor, such as higher-order understanding of concepts, instead of relying on vague definitions of what “hard” means, such as heavier workloads. She also said that considering who may be privileged or disadvantaged by the standards used to define rigor is vital for fostering more equitable and inclusive learning for all students.

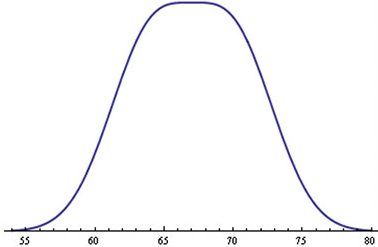

In making the point about how arbitrary using grade distribution as a way to measure rigor, McGurk shared this image of what might be considered an ideal grade distribution curve, but in fact, this particular graph was a chart of height distribution in the population. (Schinske & Tanner, 2014).

III. Rigor is not simply hard for the sake of being hard, but it is purposeful and transparent.

Finally, the third principle behind defining rigor depends on transparent communication with students about grading practices and the purpose of the learning activities in the course. Transparency may also mean uncovering some aspects of what is referred to as the “hidden curriculum” – for example, what does it mean to be a student? How should a student read for understanding or study to create enduring learning? Being transparent and purposeful about how success is defined in a course makes it more accessible for all students and supports a sense of belonging, especially for those who have been historically excluded from certain disciplines.

What Rigor is Not

According to Brooks and McGurk:

IT IS NOT a shield to criticism. Classes with higher-than-average failure rates are not more rigorous.

IT IS NOT a mechanism for training students to be irresponsibly dependent on authority. Memorizing and regurgitating large amounts of information is not rigorous. Encouraging critical thinking and challenging assumptions is rigorous.

IT IS NOT opaque or illegible expectations rather than high ones. Reducing expectations sends a message of non-inclusivity.

Rigor as Inclusive Practice

Throughout the talk, Brooks and McGurk emphasized the fact that they prefer to stay away from formulating one single definition for rigor. And instead encouraged instructors to define rigor for their own contexts and disciplines based on the three principles described above.

Brooks and McGurk believe contextual definitions of rigor will lead to the best outcomes for the students in that particular classroom. When we frame rigor as inclusive practice using these three principles, they argue, it is clear that they are not opposing forces but rather reinforce and inform each other. An inclusive and rigorous curriculum allows all students to not merely “get through” a challenging course but “thrive” in it.

References

Culver, K.C. & Braxton, J. & Pascarella, (2019). Does teaching rigorously really enhance undergraduates’ intellectual development? The relationship of academic rigor with critical thinking skills and lifelong learning motivations. Higher Education, 78, 611-627.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00361-z

Fullilove, R. E., & Treisman, P. U. (1990). Mathematics achievement among African American undergraduates at the University of California, Berkeley: An evaluation of the Mathematics Workshop Program. The Journal of Negro Education, 59(3), 463–478. https://doi.org/10.2307/2295577

Nelson, C. (2010). Dysfunctional Illusions of Rigor. To Improve the Academy.

Schinske, J. & Tanner, K. (2014) Teaching More by Grading Less (or Differently). CBE—Life Sciences Education, 13(2), 159-166.