Balancing High Expectations and Flexibility: Supporting Student and Faculty Mental Health with Compassionate Challenge

View Recording on Panopto (restricted to the MIT Community)

On Wednesday, December 13, we hosted Dr. Sarah Rose Cavanagh to discuss how to create challenging learning environments for students that also support their mental health and wellbeing.

The Landscape: “Difficult pasts, stressful presents, and uncertain futures”

Dr. Sarah Rose Cavanagh describes how students are facing “difficult pasts, stressful presents, and uncertain futures” in higher education today. The pandemic created major disruptions to schedules, social interactions, and intellectual work for faculty, staff, and students alike. Students are dealing with trauma of all sorts, not just from the pandemic, but challenges they bring from their various life experiences, such as discrimination or poverty and other “difficult pasts.” In the present, they face the pressure of figuring out their life direction, balancing work and school, and outside stressors like global conflicts, political polarization, and climate change, feeding into the feeling of a “precarious future.”

It shouldn’t be a surprise then, Cavanagh said, that many higher education publications report “stunning” levels of student disengagement (McMurtrie, 2022) and the American Academy of Pediatrics declared the first-ever “national emergency” in child and adolescent mental health (AAP-AACAP-CHA Declaration of a National Emergency in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, n.d.). Teaching and learning in this context poses a high level of challenge for instructors and students. While it may seem daunting, Cavanagh argues that we can apply lessons learned about flexibility and compassion from the pandemic and balance them with high expectations and rigor to create intellectually challenging learning environments that support students’ mental health and wellbeing. This learning environment is guided by principles that embrace what Cavanagh calls “compassionate challenge.”

Compassionate Challenge

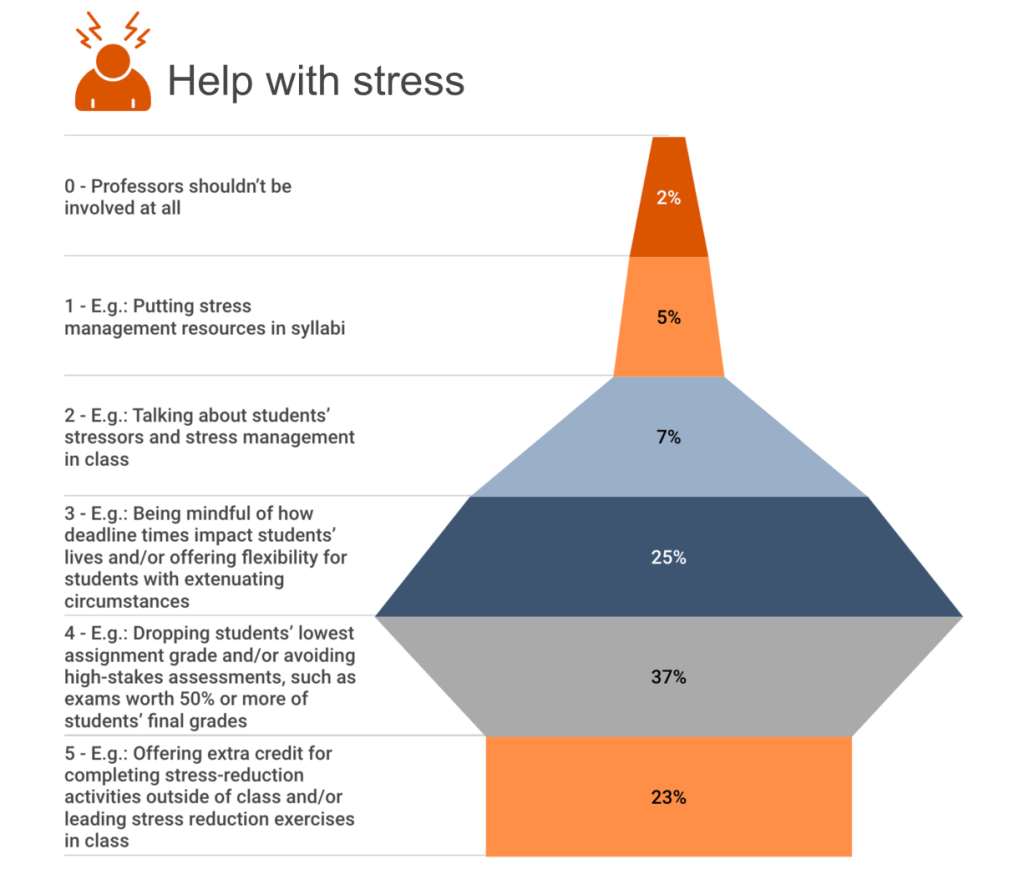

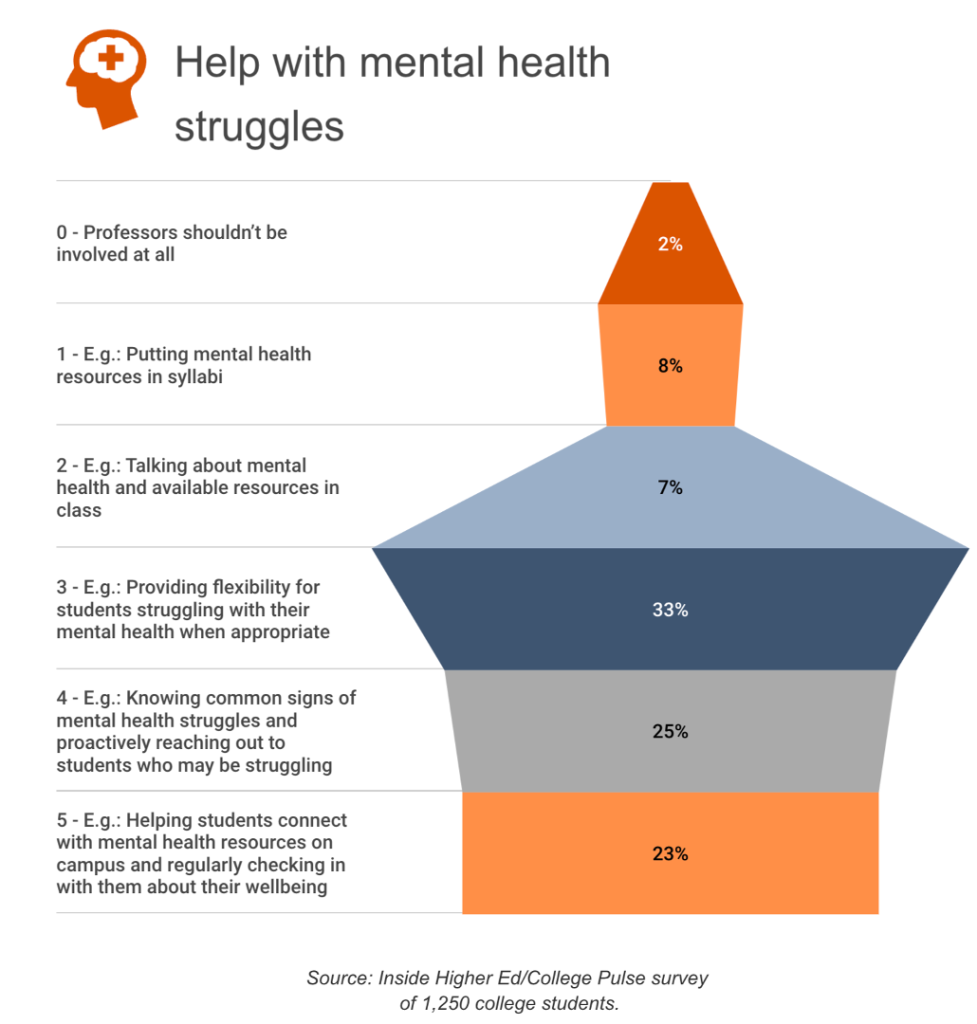

According to survey data collected by Inside Higher Ed and College Pulse, a majority of students indicated that they expected higher education to support student mental health instead of placing the responsibility solely on the individual (Flaherty, 2023). Students want more compassion, but, Cavanagh argued, they also need to be challenged in order to learn. There is an ongoing debate in academia that “rigor, intellectual challenge, and high expectations are incompatible with care, inclusion, and responsivity,” Cavanagh added, stating that this is a false dichotomy. The critical point, Cavanagh continued, is to provide a safe setting where students are challenged to learn without the expectation that they get everything right on the first try.

Compassionate challenge is achieved by providing support and routines that help students reframe the roles of uncertainty, discomfort, and failure in learning, thereby strengthening resilience. Instructors should practice “warm demandingness,” not “passive leniency” (Hammond & Jackson, 2014). A warm demander is an instructor who has high expectations, is actively demanding, and offers numerous cognitive challenges but does so with personal warmth, encouragement, and compassion (Hammond & Jackson, 2014).

Supportive learning environments

To illustrate this, Cavanagh turned to a metaphor of fabrics used in Drive to Thrive: A Theory of Resilience Following Loss (Hou, Hall, & Hobfall, 2018). The interwoven threads that support each other in fabrics are like the routines or structured activities embedded in a course, such as teaching methods or assessments strategies, that support student learning. If there are fewer threads (routines) in a fabric, pulling just a few makes the material fall apart. However, if fabrics are more complex, they can withstand pulling lots of threads and still hold together. (Hou et al., 2018). The research on resilience as a result of routine (and the analogy of fabric) reinforces what has been heard in other places: students need structures to be successful, especially in the face of stressful circumstances (Eddy & Hogan, 2017; Tanner, 2013).

Challenging and compassionate course structure

Courses shouldn’t just focus on an outcome; they should be structured to support students in achieving that outcome. To exemplify this, Cavanagh highlighted a quote from Karen Costa: “Resilience is a natural outgrowth of support. We don’t build resilience. We get correct care and support, and resilience blooms all on its own” (as cited in Cavanagh, 2023, p.115). In a challenging and compassionate course, this care and support may include low-stakes assessments, frequent feedback, and “flexibility with guardrails.” For example, students might be provided with flexible deadlines as long as assessments are completed by the end of a unit or module. Instructors could also offer staged assignments or exams that allow for revision or opportunities to drop the lowest grade on assignments or quizzes. Grading practices can also align with compassionate challenge by considering progress towards clearly defined learning goals and providing opportunities to revise after receiving helpful feedback (Clark & Talbert, 2023).

Limitations

In closing, Cavanagh emphasized that instructors are not clinicians. Rather than attempt to treat mental illness, they must create learning environments that support student mental health and wellbeing. Instructors should also know the limits of their role and set appropriate boundaries that protect their own wellbeing. “Boundaries are the distance at which I can love you and me simultaneously.” Prentis Hemphill, writer, embodiment teacher, conflict facilitator.

Resources

TLL

- Rigor as Inclusive Practice | Teaching + Learning Lab

- Trauma-Informed Teaching | Teaching + Learning Lab

- Help Students Retain, Organize and Integrate Knowledge | Teaching + Learning Lab

- Assess for Learning | Teaching + Learning Lab

- How to Give Feedback | Teaching + Learning Lab

Journal Articles

- Emotional Well-Being: What It Is and Why It Matters

- Meta-affective learning in an introductory physics course

References

AAP-AACAP-CHA declaration of a national emergency in child and adolescent mental health. (n.d.). https://www.aap.org/en/advocacy/child-and-adolescent-healthy-mental-development/aap-aacap-cha-declaration-of-a-national-emergency-in-child-and-adolescent-mental-health

Clark, D., & Talbert, R. (2023). Grading for Growth A Guide to Alternative Grading Practices that Promote Authentic Learning and Student Engagement in Higher Education. Routledge.

Eddy, S. L., & Hogan, K. A. (2017). Getting under the hood: How and for whom does increasing course structure work? CBE- Life Sciences Education, 13(3), 453–468. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.14-03-0050

Flaherty, C. (2023, July 17). Supporting Student Wellness: What’s Enough and What’s Too Much? Inside Higher Ed.

Hammond, Z., & Jackson, Y. R. (2014). Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain: Promoting authentic engagement and rigor among culturally and linguistically diverse students. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB18777744

Hou, W. K., Hall, B. J., & Hobfoll, S. E. (2018b). Drive to Thrive: A Theory of Resilience following loss. In Springer eBooks (pp. 111–133). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97046-2_6

McMurtrie, B. (2022, April 5). A ‘Stunning’ level of student disconnection Professors are reporting record numbers of students checked out, stressed out, and unsure of their future. https://www.chronicle.com. Retrieved February 12, 2024, from https://www.chronicle.com/article/a-stunning-level-of-student-disconnection

Tanner, K. D. (2013). Structure matters: Twenty-one teaching strategies to promote student engagement and cultivate classroom equity. CBE- Life Sciences Education, 12, 322-331. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.13-06-0115