Finding the Why: Integrating Purpose in STEM as a Path to Student Engagement

View recording on Panopto (restricted to MIT community).

On Thursday, September 28, 2023, we hosted Dr. Amanda Diekman to discuss how considering students’ “why” in pursuing STEM fields provides a valuable vantage point to foster both broader participation and deeper engagement in STEM.

What motivates students to pursue a career in STEM? What do STEM “environments” signal to students about the goals students can fulfill in the field? Furthermore, how is this related to the gender imbalance that persists in certain STEM professions? Over the past 15 years, Prof. Amanda Diekman has addressed these and related questions through research in her labs at IU and Miami University. Her work seeks to identify ways to foster broader participation and deeper engagement in STEM fields.

Communal Orientation Predicts Career Interest

Diekman began by highlighting a Nature essay (Leeming, 2018) calling on early career scholars in STEM to “persevere to find meaning in their work.” More recently, a 2022 survey of STEM professionals conducted by 3M1 also supports this finding. When asked, “What is your inspiration for pursuing a STEM career?” most respondents cited passion for the field, being in a respected field, solving the world’s biggest challenges, and making a difference. However, there were apparent demographic differences in the results:

- White men described personal or agentic goals such as “passion for the field” and “being in a respected field.”

- White and Black women and Black and Hispanic men were more likely to choose “solving the world’s biggest challenges” and “making a difference,” which are altruistic or communal goals.

These patterns are consistent with the work on goal congruity and student beliefs Diekman and her team have studied for the last 15 years. For example, in a correlational study that compared a student’s career interest with their communal goal orientation, Diekman found that when students endorsed a communal goal orientation, they also expressed increased interest in female-stereotypic careers and lower interest in STEM ones. There was no relationship between goal orientation and male-stereotypic careers. Though correlational, these data show that differences in communal goal endorsement partially explain the variance in pursuing STEM careers (Diekman et al., 2010, 2011, 2020).

1 3M’s State of Science Index is a global, third-party research study that explores how people view a range of science-related topics.

Goal Congruity Theory

Diekman theorized that goal congruity theory may play a part in why students may (or may not) choose to go into STEM fields. There are two central premises of goal congruity theory:

- Fundamental motivations drive behavior; everyone possesses some degree of each, depending on the context. Motivations can vary by individuals and by groups. These fundamental motivations are categorized into two major dimensions:

- Agentic goals are self-oriented and include acquiring power, skill development, and self-direction.

- Communal Goals: These goals are other-oriented and include helping others in society, working closely with others, and being altruistic.

- Contexts and roles are perceived to afford goals differentially. In other words, the decision of individuals to engage in certain roles depends on their expectations of those roles and the value they attach to them (Diekman et al., 2017, 2020).

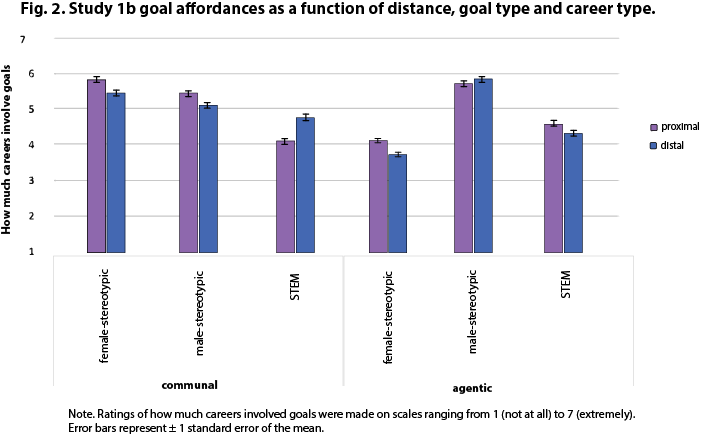

STEM environments clearly communicate agentic opportunities: Women and men in STEM equally report their desire to be competent, to have power, and to be financially successful (Diekman et al., 2017, 2020). However, what about communal opportunities, which tend to be held by people from more minoritized groups? To answer this question, Diekman and her team surveyed a wide range of undergraduate students across different majors and asked them to rate several career pathways (Diekman et al., 2010, 2011, 2020)

In the survey, students rated career pathways according to how each fulfilled communal goals (intimacy, affiliation, and altruism) and agentic goals (power achievement, seeking new experiences, or excitement.) Overall, students perceived STEM fields as less likely to fulfill communal goals than agentic ones. In male-stereotyped fields with equal representation of men and women, like law and medicine, students rated them as equally fulfilling agentic and communal goals. Furthermore, female-stereotyped careers were perceived as especially likely to fulfill communal goals and less likely to fulfill agentic goals (Diekman et al., 2010)

The finding that STEM careers are perceived to be less likely to advance communal goals has been consistently replicated over multiple studies. This belief is consistent across student age, gender, ethnicity, and major (STEM or otherwise) and includes those training to be math or science teachers. Though these beliefs tend to lessen over time for STEM students who persist in their study, it is especially prevalent for first and second-year engineering and physical science majors (e.g., physics, astronomy, and chemistry. Student perceptions of fields in the Life Sciences (e.g., biology, psychology, and medicine) tend to be more balanced (Diekman et al., 2010, 2011, 2020).

What about the STEM environment specifically might be signaling communal or agentic goals to students? Diekman and her team analyzed online course assignments to compare engineering and physical sciences with life sciences across a university system over several years. They found that life sciences environments offered more collaborative activities, discussion boards, and peer reviews than those in engineering or physical science, which matched what the students had reported about their beliefs about goal affordances in these fields (Joshi et al., 2022).

The finding that STEM students perceive communal opportunities in life sciences and advanced engineering and physical sciences clearly shows that STEM fields can afford communal goals. The important question next is how to signal these communal opportunities earlier and to a broader range of students.

Changing Perceptions About STEM Careers

Diekman presented the findings of a study her group designed to determine whether or not a communal framing of a science career could increase positivity towards STEM in early college students. The students read a description of the daily tasks of a scientist and were randomly assigned to two groups. The control group read descriptions of the functions the individual would complete on a typical day. The experimental group read a similar description of tasks, except it included references to the people or groups they would interact with within the workplace. For example, “I usually have to check a database maintained by the Operations Group” vs. “I usually have to communicate closely with the Operations Group.” Then, students wrote about their interest in the careers referenced in those readings. The results showed that a communal framing of job descriptions increased interest in STEM careers, especially for female students. Based on this finding, Diekman argued that communal framing “… offers us a new lever to engage students and to engage different students” in pursuing STEM pathways (Diekman et al., 2011).

Diekman added that the positive effects of communal affordances on perceptions of STEM environments are not limited to binary gender disparities discussed in the above research. Over a decade of data collection has consistently shown that communicating the existence of pro-social opportunities increases interest in STEM careers for everyone, including those from historically underrepresented minorities (URMS) and first-generation/low-income (FGLI) students.

Adapted from “Considering “why” to engage in STEM activities elevates communal content of STEM affordances,” by Steinberg, M., and Diekman, A. B., 2018 Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 75, 107–114. (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2017). Copyright 2017 by Elsevier Inc.

Considering the Why

Why vs. How

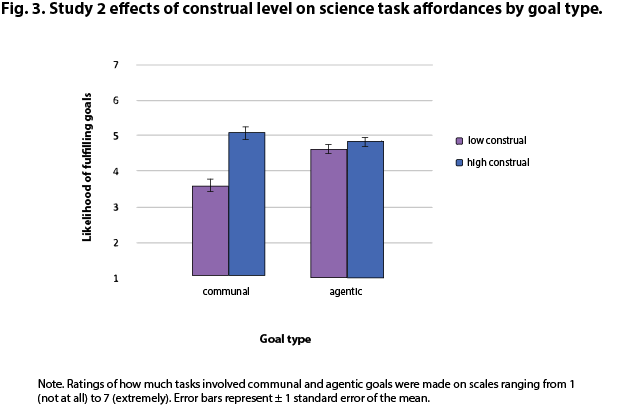

The final two studies Diekman discussed examined whether students could be directed to think about STEM fields as affording opportunities that align with their values and fulfill both communal and agentic goals. In both studies, participants thought about purpose – the purpose of the field and their purpose in the field. In Steinberg & Diekman (2018), participants responded to prompts about the purpose of conducting a scientific experiment. Students randomly assigned to the lower construal group explained “how” scientists conduct experiments. Students randomly assigned to the high construal group described “why” scientists conduct experiments. Then, each group rated the content of the tasks they generated based on how communal or agentic they were.

The results showed that students in the higher construal “why” saw science as offering both communal and agentic goals and reported more positive attitudes toward entering STEM fields. In contrast, students in the lower construal condition saw science as less communal than agentic. Diekman explained that this was one of the first indications that students could be directed to identify how STEM fields could afford communal goals. “We don’t have to tell them that science is different. They can reach those explanations if we direct them towards them [communal goals].”

Adapted from “Considering “why” to engage in STEM activities elevates communal content of STEM affordances,” by Steinberg, M., and Diekman, A. B., 2018 Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 75, 107–114. (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2017). Copyright 2017 by Elsevier Inc.

Challenge vs. Purpose

Because the gap in perception of STEM fields as agentic v. communal is widest in the early years of college, particularly in engineering and physical sciences, and especially among URM and FGLI students (e.g., Allen et al., 2015; 2018), Diekman and her team investigated whether helping students view their challenges in context might improve their attitudes toward STEM fields. Diekman and her team investigated whether helping students view their challenges in context might improve their attitudes toward STEM fields in an experimental2 study of 466 students, half from minoritized racial identities and gender-balanced within those categories. Students were randomly assigned a brief reflection activity – they were either asked to write about their challenges in STEM or their challenges as integrated with their purpose in STEM. (White & Diekman, 2023)

Recognizing challenges was critical given that STEM majors are demanding, especially for historically underrepresented students, so both prompts acknowledge that college can be difficult and stressful. The control prompt asked students to write about the challenges they faced in their training and how they affected their everyday lives. However, the purpose reflection framed these challenges in the context of being “worth it” when doing something that matters, and they were asked to write about what they wanted to do with their training and what about their career path was important to them. The results of this experiment showed “a whopper of a main effect of purpose reflection” – students who reflected on their purpose reported feeling like they fit in as their true selves in their major, while students who only reflected on challenges reported “fitting in” significantly less. For the first time, Diekman also measured the stress levels of participants. The direction of the effect was the same – students reflecting on purpose reported lower stress levels than students only reflecting on challenges.

Aside from this main effect, there were also interesting interactions. For example:

- White and Asian men started with low levels of stress; after the purpose reflection, they reported that their capacity to cope surpassed their stress.

- White and Asian women started with higher levels of stress than their male counterparts; after the purpose reflection, they reported an increased capacity to cope.

- Men of color start with higher levels of stress than their white and Asian counterparts but less than that of white and Asian women; after the purpose reflection, they report an even greater capacity to cope with their stressors than any of the other groups.

- Women of color, on the other hand, start with the highest levels of stress; even though they report an increased capacity to cope after the purpose reflection, they report that they are still feeling less able to cope.

2 White, A., Diekman, A.B., (2023). Student Reflections on Purpose in STEM. Under review. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/68FGB

Figure 2. This is a bar graph that shows the interaction effects between agentic and communal goal affordances for proximal and distal goals based on the career: female-stereotypic, male-stereotypic, and STEM. The key result portrayed by the graph is that STEM careers, compared to other types, are relatively low in communal affordances for goals in the near future while STEM careers are perceived to provide communal affordances for goals farther in the future.

Conclusions

Diekman’s research has provided strong evidence across race and gender that reflecting on their purpose in STEM helps students perceive opportunities that fulfill communal as well as agentic goals. However, Diekman also stated that students are entering with vastly different and varying amounts of stress. Moreover, while this tool is helpful, it is important to remember that the playing field is still not level.

Based on the evidence accumulated over 15+ years, Diekman concluded that students can articulate purpose and see goal opportunities when we “nudge” them to think about it and persevere to find meaning in their work. If we want a vast, talented, and diverse workforce in STEM, educators, administrators, and others in positions of authority must signal these opportunities and create space in the classroom for students to pursue and fulfill these goals in STEM fields.

References

Allen, J. M., Muragishi, G. A., Smith, J. L., Thoman, D. B., & Brown, E. R. (2015). To grab and to hold: Cultivating communal goals to overcome cultural and structural barriers in first-generation college students’ science interest. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 1(4), 331–341. https://doi.org/10.1037/tps0000046

Allen, J., Smith, J. L., Thoman, D. B., & Walters, R. W. (2018). Fluctuating team science: Perceiving science as collaborative improves science motivation. Motivation Science, 4(4), 347–361. https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000099

Diekman, A. B., Brown, E. R., Johnston, A. M., & Clark, E. K. (2010). Seeking congruity between goals and roles: A New look at why women opt out of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics careers. Psychological Science, 21(8), 1051-1057. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610377342

Diekman, A. B., Clark, E., Johnston, A. M., Brown, E. R., & Steinberg, M. (2011). Malleability in communal goals and beliefs influences attraction to stem careers: Evidence for a goal congruity perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(5), 902–918. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025199

Diekman, A. B., Joshi, M., & Benson‐Greenwald, T. M. (2020). Goal congruity theory: Navigating the social structure to fulfill goals. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (pp. 189–244). https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aesp.2020.04.003

Joshi, M., Benson‐Greenwald, T. M., & Diekman, A. B. (2022). Unpacking motivational culture: Diverging emphasis on communality and agency across STEM domains. Motivation Science, 8(4), 316–329. https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000276

Steinberg, M., & Diekman, A. B. (2018). Considering “why” to engage in STEM activities elevates communal content of STEM affordances. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 75, 107–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2017.10.010

White, A. D., & Diekman, A. B. (2023, May 20). Student Reflections on Purpose in STEM. Under review https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/68FGB