How to overcome Zoom’s algorithmic bias

Have you ever wondered what determines the arrangement of participant thumbnails in Zoom’s Gallery View?

By default, the order of participants changes over the course of a Zoom meeting. As participants join the call, their thumbnail display is added to the grid of participants in the order of arrival. Then, throughout the call, participants are reordered to the front (i.e., the top left of the grid) as they speak.

The Gallery View allows for 49 participants to be shown per page, so the result of Zoom’s placement algorithm is that the most dominant speakers are most prominently featured on the first page. From a teaching and learning perspective, Zoom’s ordering algorithm is problematic — especially if students are not aware of the reasons behind this positioning.

Consider inequities in student speaking time

A recent study by Lee & McCabe in Gender & Society found that men are 1.6 times more likely to participate verbally in a college classroom than women, concluding that “these gendered classroom participation patterns perpetuate gender status hierarchies.”

A 2016 Brown University study found that 86 percent of white students, compared to less than 80 percent of Hispanic, Asian, and Black students, felt somewhat or very comfortable speaking up in class. Eddy & Hogan, 2019 found that Black students in traditional lecture classes were “2.3 times more likely to report a lower level of in-class participation than students of other ethnicities.”

As Tanner, 2013 states in Structure matters: Twenty-one teaching strategies to promote student engagement and cultivate classroom equity:

“Many studies have documented that students from a variety of backgrounds in undergraduate science courses experience feelings of exclusion, competitiveness, and alienation (Tobias, 1990; Seymour and Hewitt, 1997; Johnson, 2007). Research evidence over the past two decades has mounted, supporting the assertion that feelings of exclusion—whether conscious, unconscious, or subconscious—have significant influences on student learning and working memory, as well as the ability to perform in academic situations, even when achievement in those academic arenas has been documented previously (e.g., Steele and Aronson, 1995; Steele, 1999).”

These findings underscore a potential bias with Zoom’s participant ordering algorithm and invite consideration of the following questions:

- If less vocal students only see a subset of more vocal students on their first screen, what message does this send about who is more or less valued in the class?

- If the students that speak most often are from a particular demographic (e.g., white, male, graduate students), what unintended message might this send about who does or doesn’t belong in your classroom?

- How might Zoom’s algorithm impact the perceived composition of the class if students see one particular group being dominantly represented onscreen? For underrepresented students, this can exacerbate feelings of stereotype threat.

How to override Zoom’s algorithm

To prevent these unintended consequences of algorithmic bias, you can intervene to reflect a more inclusive visual of your class back to your students by making one small change.

As the host of your Zoom meeting, you can prevent the grid from changing as students speak. Instead, the layout of your participants’ thumbnail displays will be dictated by the order in which they arrive.

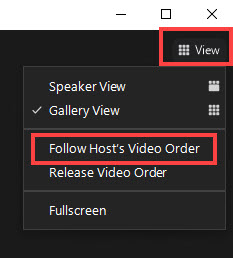

1. First, you need to click View ![]() to switch from Speaker View to Gallery View. In Gallery View, you can click and drag the video thumbnails to create a custom order.

to switch from Speaker View to Gallery View. In Gallery View, you can click and drag the video thumbnails to create a custom order.

After you make the first change, all other participant tiles will remain in place until moved. This prevents Zoom’s algorithm from reordering the layout as participants speak.

2. If you have time to fix your configuration before your students join the Zoom meeting, you will still need at least 2 participants to enable the Gallery View. In this case, you can either join the call on 2 devices, or with a co-instructor, and simply switch the order of your videos.

Your new custom order will apply to the Gallery View as well as the active Speaker View for participants using the desktop client, mobile app, or Zoom Rooms.

3. As the host, you can then ensure that all participants have the same fixed layout that you see. Again, click View and confirm that Follow Host’s Video Order in the dropdown menu is checked. this forces the view for all participants to display your custom video order. when non-video participants enable their video, they will be added to the last page of the gallery view, in the bottom-right corner spot.

Please note that participants will not be able to change the order once Follow Host’s Video Order is enabled. To disable this fixed layout, you can click Release Video Order, reverting all views to the default order and allowing again for Zoom’s ordering algorithm to affect the layout.

Communicate your intentionality

If you decide to lock the layout of participant tiles, you may want to be explicit with your students about why you have deliberately made this change to intentionally promote inclusivity.

Alternatively, if you decide not to override the default Zoom algorithm, you may want to:

- Make clear to your students that the Zoom algorithm prioritizes showing participants who speak by reordering their thumbnail displays towards the top left of the grid.

- Point out that although verbal in-class participation is (presumably) an important component of the class, you value and welcome all students’ engagement and involvement in the course.

- Provide a variety of ways for students to pose questions, contribute responses, and otherwise participate in the course.

- Find ways to acknowledge and publicly value student contributions, such as:

- Questions in the chat or another backchannel application

- Contributions to a class discussion board

- Post-class Mud Cards or Exit Tickets

- Proactively work to promote verbal participation from a larger group of students. Tanner, 2013 provides an excellent collection of strategies to increase student participation, such as:

- Providing “wait time” before calling on a student to answer a question. This gives students the opportunity to formulate their responses before speaking

- Enforcing hand-raising. This will help ensure that not only students who are comfortable jumping in have opportunities to provide comments

- Requiring multiple raised hands (e.g., Require that at least 3 students have raised their hands to respond before you will call on a student. This will allow you to call on students who are not the most frequent and/or fastest responders.)

- Calling randomly on students (e.g., Use index cards with students’ names and be explicit about what you are doing and why to bring more student voices into the classroom interactions. The random aspect of this strategy can help minimize students’ sense that any student is being “singled out,” positively or negatively.

Written by Janet Rankin & Ryan MacDowell

References

Lee JJ, Mccabe JM. Who Speaks and Who Listens: Revisiting the Chilly Climate in College Classrooms. Gender & Society. 2021;35(1):32-60.

Comfort Speaking in Class Varies with Gender and Ethnicity, Brown Daily Herald, 2016.

Eddy SL, Hogan KA. Getting under the hood: How and for whom does increasing course structure work? CBE—Life Sci Educ. 2014;13: 453–468.

Tanner, K.D. (2013). Twenty-one teaching strategies to promote student engagement and cultivate classroom equity. CBE – Life Sciences Education, 12: 322-331.

Tobias S (1990). They’re not dumb. They’re different. A new tier of talent for science. Change 22, 11–30.

Seymour E, Hewitt NM (1997). Talking about Leaving: Why Undergraduates Leave the Sciences, Boulder, CO: Westview.

Johnson A (2007). Unintended consequences: how science professors discourage women of color. Sci Educ 91, 805–821.

Steele CM, Aronson J (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. J Pers Soc Psychol 69, 797– 811.Steele CM (1999). Thin ice: stereotype threat and black college students. Atlantic Monthly August, 44–54.